NAIROBI,Kenya – The intersection of data acquisition and digital incentives has raised significant ethical and practical questions, particularly in developing regions where economic instability can make seemingly advantageous offers more tempting for residents. One such case that illustrates these concerns is the recent expansion of Worldcoin in Kenya. Worldcoin, a cryptocurrency project founded by Sam Altman, aimed to address issues of digital identity and financial inclusion by providing a unique offering: biometric data in exchange for cryptocurrency.

However, while the program may have appeared beneficial at first glance, it highlighted deeper, systemic challenges. Specifically, the initiative’s design raised critical questions about informed consent, the valuation of personal data, and the potential for exploitation in the process of obtaining biometric information.

At the core of the Worldcoin project was an incentive structure where people were encouraged to share their biometric data, specifically iris scans, in exchange for a small amount of cryptocurrency. For many Kenyans, the promise of a digital financial reward was enticing, as economic opportunities in certain regions remain limited, and financial inclusion efforts have been inconsistent. Cryptocurrency, for some, appeared to be a potential gateway to accessing the global financial system. However, beneath the surface, concerns regarding the true cost of this exchange surfaced quickly.

One of the primary issues with Worldcoin’s approach was the inadequate transparency about the risks associated with sharing biometric data. While the prospect of earning cryptocurrency might be easily understood, the intricacies of biometric data value, its permanence, and the long-term implications of its collection are complex. Unlike financial data, which can be changed or protected through encryption, biometric data is inherently unique and cannot be altered once it has been captured.

This means that the individuals participating in such exchanges may face irreversible risks if this data is misused, mishandled, or compromised. In Kenya, there was significant concern that people were not given enough information about how this data would be stored, who would have access to it, and the potential future implications of surrendering this deeply personal information.

Moreover, the exchange of biometric data for cryptocurrency in economically vulnerable communities raises ethical questions regarding consent. When people are motivated by financial need, they may be less likely to scrutinize the long-term consequences of their decisions.

The Worldcoin case in Kenya highlighted the possibility that participants did not have a real choice; instead, they were compelled by economic circumstances to accept an offer that wealthier individuals with more resources might have turned down. This potential for exploitation was particularly pronounced in areas where trust in institutions is already low, and where historical inequities have shaped a landscape where people are often offered minimal choices for personal advancement.

Beyond issues of transparency and informed consent, the Worldcoin case in Kenya underscored the challenge of valuing biometric data appropriately. Cryptocurrency, by its very nature, is volatile, and the value of the compensation provided to participants could fluctuate drastically.

In some cases, Kenyans who participated in the program found that the value of their cryptocurrency rewards did not retain stable value over time, potentially diminishing the already minimal compensation they had received. This speculative reward mechanism contrasts with the permanent and sensitive nature of biometric data, creating an inequitable exchange that ultimately may fail to respect the intrinsic worth of the data being surrendered.

The Worldcoin initiative has led to calls for more robust regulations and safeguards around data exchange in Kenya. Critics have urged that people be given sufficient education about the value of their biometric data and that regulatory bodies establish standards for data collection practices, especially when sensitive data is involved. They argue that offering short-term rewards for long-term data consequences, without adequate consumer protection mechanisms, could pave the way for a type of digital colonialism, where corporations leverage their technological resources to extract valuable data from vulnerable populations.

In summary, while incentivizing data collection with digital rewards has the potential to drive greater financial inclusion, the Worldcoin case in Kenya demonstrates that without careful oversight and education, such initiatives risk exploiting rather than empowering participants.

To protect individuals in similar scenarios, particularly in regions where digital literacy may vary significantly, it is essential to prioritize transparency, informed consent, and adequate compensation. Moving forward, policies should focus on safeguarding citizens’ biometric data rights and ensuring that any incentives offered reflect the true value and potential risks associated with this deeply personal information.

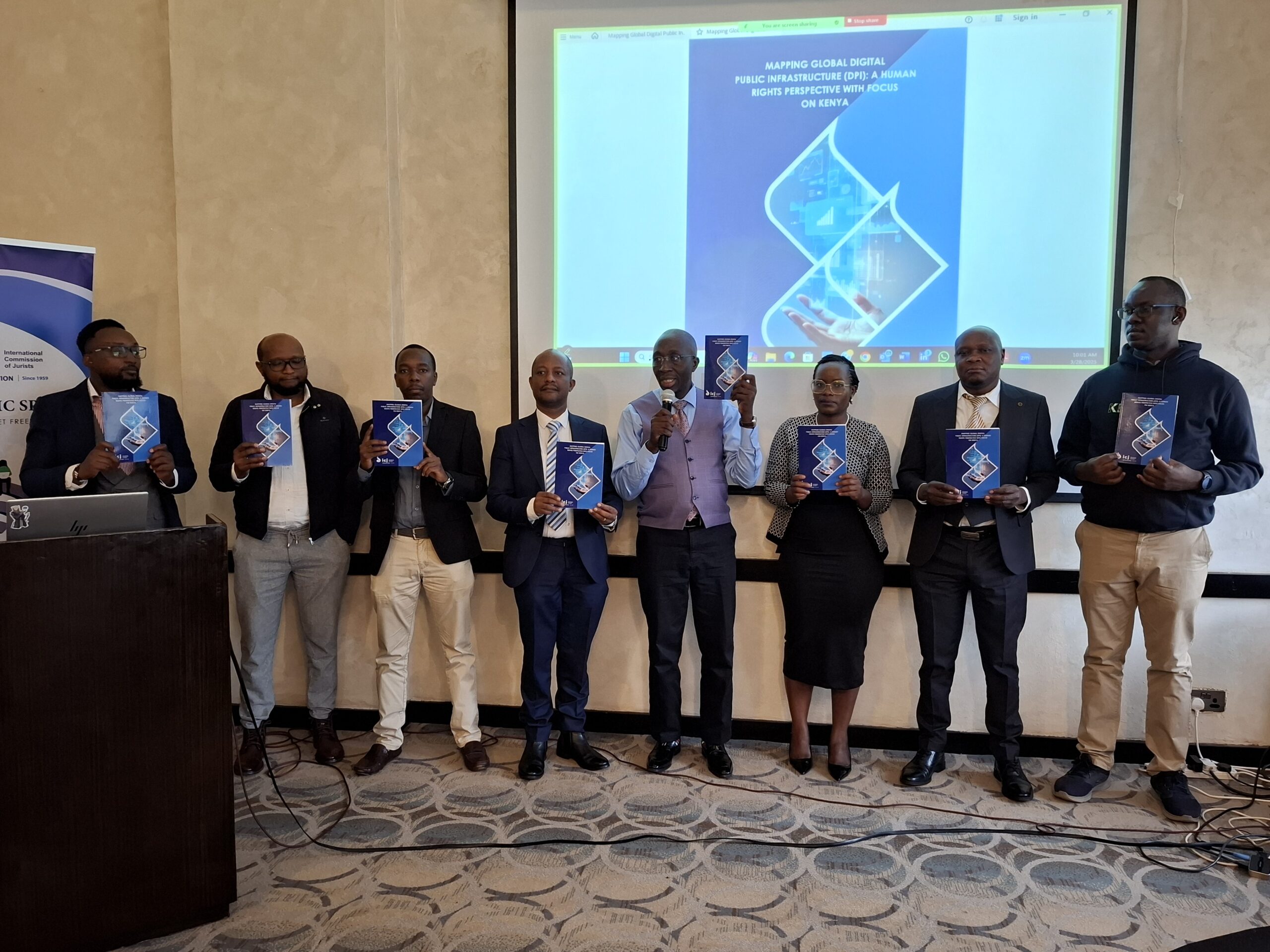

The writer, Charles Jaika is a Programme Consultant at ICJ Kenya.