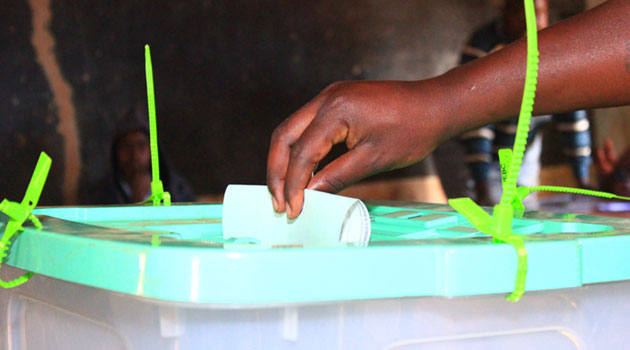

NAIROBI,Kenya – Kenya’s elections are not just an event; they are an industry, a multi-billion-shilling spectacle that drains the taxpayer while delivering suspicion, tension, and, ultimately, political settlements. With the IEBC now requesting Ksh.61.7 billion to conduct the 2027 General Election, it is fair to ask, what exactly are we paying for?

This is not the first time the electoral body has tabled a jaw-dropping budget, nor will it be the last. Over the years, the cost of elections has soared, making Kenya one of the most expensive democracies in the world. Yet, for all this spending, what do we get in return? The cycle is predictable, billions poured into technology, voter registration, polling logistics, and legal fees, only for the final outcome to be contested, dragged through the courts, and resolved in closed-door negotiations.

It doesn’t matter how much we spend; the outcome is always the same. The losing side rejects the results, heads to court, and after days of dramatic litigation, a verdict is delivered, often followed by protests, teargas, and the now-infamous call for “national dialogue.” In the end, a handshake, a broad-based government, or some form of political truce is reached, and life moves on, until the next election, when we rinse and repeat. If that is the case, shouldn’t we just budget for a handshake from the outset and save Kenyans the billions?

What makes this even more laughable, if it weren’t so tragic, is that no matter how many billions are spent, elections in Kenya remain a high-risk venture. The costs we can quantify; billions on technology, personnel, and materials are just the tip of the iceberg. The unspoken cost is the blood, the lives lost, the homes burnt, the businesses destroyed, and the fear that grips the nation every election cycle. The price of democracy in Kenya is not just counted in shillings but in graves and broken dreams.

The IEBC justifies its budget by citing technological advancements, logistical complexities, and a growing electorate, but these reasons do little to explain why Kenya spends more per voter than many other countries with similar electoral demands. South Africa, with nearly the same number of voters as Kenya, conducts its elections at a significantly lower cost. Even Nigeria, with nearly four times the number of voters, manages to spend less per voter than Kenya. So, what exactly makes our elections so expensive?

Technology is often sold as the magic solution, but in Kenya, it has become part of the problem. The KIEMS kits, electronic voter identification, and transmission systems have consistently failed at critical moments, leaving the country in limbo as court battles rage. After all, why should an election end at the ballot box when it can be fought in the Supreme Court, in press conferences, and, if all else fails, in the streets? If technology was meant to solve disputes, it has failed spectacularly. Instead, it has made elections more expensive without necessarily making them more credible.

And then there’s the trust deficit. It doesn’t matter how much we spend, if Kenyans do not trust the process, elections will always be a disputed, high-stakes gamble. We could spend twice as much, triple even, but without electoral reforms that inspire faith in the system, we are simply throwing good money after bad. We are funding an illusion, an expensive performance that leaves the country just as divided as before.

Perhaps what we should be asking is not how much an election costs but why we continue to pay so much for a broken system. Should elections be about how much money we can pour into them, or should they be about ensuring a transparent, credible process that citizens believe in? Should we continue to invest billions in a system that guarantees nothing but conflict, or should we be investing in electoral reforms that prioritize trust and fairness over expensive gadgets?

At this rate, Kenya will not just be the most expensive democracy in Africa, it will be the most expensive joke. A democracy where the votes are counted, but the real decision is made elsewhere. Where elections are not the solution, but the problem itself. Where the cost of voting is high, but the cost of losing is even higher.

And so, as the IEBC tables its budget, Kenyans should ask: Are we funding democracy, or are we just paying for another five-year political circus?

Thuku Mburu is a lawyer and a Programme officer at the Kenyan Section of the International Commission of Jurists (ICJ Kenya). This article was first published on the Daily Nation.