RESPONSE TO THE NATIONAL TASKFORCE ON IMPROVEMENT OF

TERMS AND CONDITIONS OF SERVICE AND OTHER REFORMS FOR

MEMBERS OF THE NATIONAL POLICE SERVICE AND KENYA

PRISONS SERVICE

TASK FORCE REPORT WELCOME BUT SHORT ON HUMAN RIGHTS

PROTECTION AND COMMUNITY POLICING.

INTRODUCTION

Background

On 22nd December 2022, President William Ruto appointed former Chief Justice David Maraga to chair a 23-member taskforce on the improvement of terms and conditions of service and other reforms for members of the National Police Service and Kenya Prisons Service. On 30th January 2023, the taskforce began collecting views from various stakeholders, including members of the public and civil society organisations.

On 3rd February 2023, the PRWG-K presented its memorandum before the Taskforce at Bomas of Kenya, where we highlighted and made recommendations regarding police welfare, professionalism, independence and capacity, accountability, quality of service, and police-community relationships and crime prevention.

Our presentation and memorandum noted that police reform issues are not necessarily legal. Rather, they are mainly due to a lack of political will, a predisposition to regime policing instead of democratic policing and a lack of transformational leadership at the top police command.

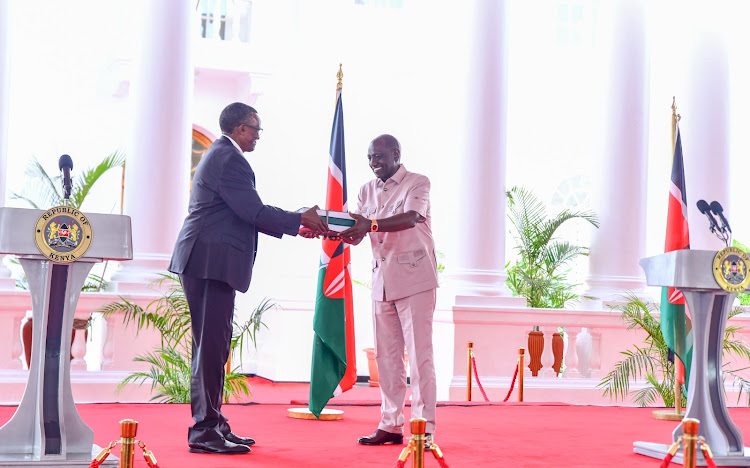

On 16th November 2023, the taskforce presented its final report to President William Ruto at State House Nairobi. The report made various findings and recommendations. This response focuses on the findings and recommendations based on the publicly available Executive Summary concerning only policing (not the complete report and annexures) as follows: –

Human Rights Violations and Accountability

The PRWG-K notes that while the report is progressive and has correctly diagnosed some issues and made recommendations thereto, it failed to appreciate and engage on the problem of gross human rights violations, and highlight human rights compliance as an overarching and endemic problem at the centre of policing in Kenya.There was no analysis of the impact of rogue policing on the lives of Kenyans, especially those from poor urban areas or far-flung areas who bear the brunt of unlawful policing. The report does not mention the assault, unlawful use of force, torture, extra-judicial killings and enforced disappearances that bedevil the NPS.

What informed the 2010 constitution and police reforms in Kenya was a desire for human rights-compliant policing after systemic human rights violations since independence. Part of the impetus for the taskforce was the public admission that there existed units within the police that engaged in Extra Judicial Executions (EJEs) and Enforced Disappearances (EDs) by none other than the President of Kenya, which is confirmed by numerous reports by human rights organisations, including the Missing Voices initiative.

https://www.missingvoices.or.ke/statistics,and, and the Independent Medico-Legal Unit(IMLU),https://imlu.org/2023/09/kenyas-human-rights-situationdisturbing-chronicles-of-broken-promises-and-human-rights-violations/,

https://imlu.org/2023/11/state-of-the-nation-2022-torture-and-related-violations-inkenya/.

We note that the report was silent on human rights violations and the various policy documents establishing principles of democratic and community policing that emphasise human rights protection. PRWG-K insists that human rights compliance is a central and mandatory ingredient of policing in Kenya as the Constitution requires.

Community Policing

Article 244 (e) of the Constitution mandates the NPS to foster and promote relationships with the broader society. This mode of policing, as mandated under the NPS Act, recognises and builds upon the shared responsibility of the police and the community to ensure a safe and secure living situation. It is predicated on building trust and establishing meaningful partnerships between the police and the public through which safety and security issues can be discussed, prioritised, and solved jointly.

Community policing enhances the police’s ability to detect, pre-empt, prevent and tackle crime while engaging the public. Community Policing enables the police know and belong to the communities they serve through partnerships, trust and relationship building. In this way, they are more likely to engage in dialogue, de-escalation tactics and alternative justice mechanisms (AJS) than use force, arrest or human rights abuses.

We note that the taskforce did not mention Community policing as a part of policing strategies in Kenya, which has been neglected despite being a legal requirement.[1] PRWG-K notes that during the 2023 Cost of Living Protests “Maandamano”, areas where Station Commanders had established relationships with the communities experienced significantly less violence.

We recommend that the government and NPS provide adequate resources to implement community policing, and operationalise the County Policing Authorities, as provided in law and as ordered by the High Court in Nakuru. This remains a pivotal platform for interaction between the County Government, citizens and national security agencies. The continued resistance to the establishment of County Policing Authorities by the Ministry of Interior continues to rob the country of a huge opportunity to lay a solid basis for dialogue and consultative-based policing at the county level.

Ignoring the critical role of County Policing Authorities in community policing and the transformation of the National Police Service was a grave omission by the Task Force. National Police Service Commission (NPSC)

The taskforce has correctly diagnosed the failure of the NPSC to carry out its vital human resource management mandate of transforming the service into a professional, accountable, and human rights-compliant service through ensuring proper and fair recruitment, training, disciplinary measures, promotions, transfers and human capital management. In line with the recommendations of the Philip Waki Report on Post Elections Violence, the Phillip Alston Report on Extra-Judicial Killings and the Philip Ransley Report on Police Reforms, the 2010 Constitution was explicit that a separate, independent civilian body should carry out human resource functions.

The taskforce rightly observed that the NPSC leadership acquiesced to the continued usurpation of its constitutional mandate by the NPS leadership and its failure to formulate policies and measures to perform its mandate.

However, we disagree that the Commissioners should be removed via a negotiated exit. Instead, we strongly recommend that Article 251 of the Constitution on removing members of Chapter 15 Commissions and Independent Offices is triggered to allow the Commissioners to explain to Kenyans why they violated their oath of office and mandate in a Tribunal.

Constitutional Commissions and Independent bodies play a vital role in our constitutional structure. Kenyans should not take lightly when Commissioners surrender their power or fail to fulfil their mandate.

Commissioners’ independence, security of tenure, and salaries are ring-fenced to ensure they do not take instructions from any authority other than the Constitution. Pushing them out of office without allowing them to account for their actions is not in the country’s best interest concerning protecting government organs andinstitutions.

Moreover, the taskforce does not give guidance on what should happen to the NPS leadership, which usurped the powers of the NPSC contrary to the law and the constitution. The Inspector General has publicly taken on the NPSC and, at one time, withdrew the Commissioner’s security when they disagreed with his unilateral and public promotion of senior officers without the input of the NPSC as required by law. This is

unacceptable conduct coming from holders of constitutional offices and needs to be censured.

Role of Cabinet Secretary in NPS

PRWG-K agrees with the taskforce that the Executive, through the Cabinet Secretary of Interior and National Coordination, has been instructing and micromanaging the NPS and the IG contrary to the Constitution, which envisions a service and IG independent of the politics of the day and beholden only to the people of Kenya and the Constitution rather

than the regime.

Article 245 (4) allows the CS to lawfully and in writing give direction to the IG concerning policy matters. The CS cannot give instructions or directions about investigations of offences, enforcement of the law against a particular person or the employment, assignment, promotion, suspension, or dismissal of any member.

The continued instructions and directions by the Executive have eroded the operational independence of the service and led to the politicisation of policing, especially against those perceived to be at loggerheads with the prevailing regime or during operations such as public protests and demonstrations.

We agree with the recommendation for the CS to urgently develop a Sessional Paper on policing and reforms to guide oversight gaps and to operationalise the Police Reforms Unit fully.

Indeed, a well-structured and better-resourced Police Reforms Directorate will harness the necessary goodwill from the Service and other stakeholders and ably coordinate policing reforms within the broad spectrum.

Operational Independence

As elaborated above, the PRWG-K agrees with the taskforce that there has been operational interference by the Executive partly due to the 2014 removal of the competitive hiring of the Inspector General of the NPS via the Security Laws (Amendment Act).

We support the taskforce’s recommendation that the powers of advertising, shortlisting, interviewing, and selecting the Commander of the NPS (Inspector General), the Deputy IGs and the Director of DCI be reverted to the NPSC.

Furthermore, we commend the taskforce for recommending an amendment of Section 87 of the NPS Act to establish competitive recruitment of the Director of the Internal Affairs Unit (IAU), ringfence its mandate to enforce discipline and professional standards and clarify that IAU only deals with disciplinary actions to avoid overlap with IPOA and DCI mandate to deal with criminal behaviour in the NPS.

We also recommend that the IAU be provided with an independent budget vote to enhance its operational efficiency and effectiveness.

Entry and Career Progression

The taskforce has correctly noted that the Security Laws (Amendment) Act was detrimental to the NPS because it deprived the Service of competent, strategic and visionary leadership by making them presidential appointees, effectively making them beholden to the regime rather than the constitution and sovereign people of Kenya. This, coupled with a dysfunctional NPSC, compromised standards of professionalism and

fairness in recruitment training, promotion, and deployment.

To embrace professionalism, the taskforce recommended raising the minimum qualifications for recruitment to C minus (C -) in KCSE and D plus (D +) for marginalised areas. However, the different entry-level qualifications should be considered in career progression lest the process renders itself discriminatory. A sunset clause for this affirmative provision would be a good starting point. We recommend that these measures be anchored in law.

We also agree with the taskforce for changes in regulations to limit operational deployment of officers to 6 months and regular deployment for a maximum of 3 years in one County.

Corruption

PRWG agrees with the taskforce’s observation that corruption in the NPS is deeply embedded and endemic in every facet of policing, including recruitment, transfers, deployment, and career progression.

Corruption in terms of taking bribes from the public, police roadblocks, traffic stops, extortion of business premises such as bars and gambling joints and unlawful arrests for purposes of extortion have become part of Kenyan life. We recall that the current Inspector General, Japhet Koome, publicly confessed in September 2023 that “returns” or daily collections are rife and that some of his juniors offered him money.

PRWG-K notes that the daily collection of “returns” from members of the public and businesses by junior police officers for upward delivery to superiors threatens businesses and security in Kenya because it compromises crime detection and prevention time.

Such activities are the preserve of criminal gangs such as the Mafia in Southern Italy or local criminal gangs, who demand protection money from residents and business people where the government has failed. It is unfortunate that in Kenya, it is a government organ

itself doing it.

PRWG-K supports the task force’s recommendation to abolish roadblocks and replace them with mobile patrol units and rapid response strategies along highways. This should be done via appropriate legislation to remove roadblocks and to remove the discretion of establishing them from the IG.

Further, the PRWG-K recommends that the NPS implements the provisions of the Bribery Act 2016 by immediately: I. Conducting a corruption risk assessment within the Service and rolling out an anticorruption strategy to manage all identified risks. This should include addressing conflict of interest areas such as police ownership and engagement in businesses and activities that compromise their impartiality and professionalism, as identified in the report.

II. Setting up an effective whistleblower protection mechanism to encourage confidential reports from citizens and officers on corruption-related matters.

We observe that the taskforce has not offered solutions to end endemic corruption in the service partly because it is a complicated issue. However, there has never been a sustained effort to investigate, prosecute and follow up on massive graft/corruption, especially at the street level.

We support the taskforce recommendation of using technology in traffic management, detecting traffic infractions and paying fines. We further recommend digitising Occurrence Books in all police stations to minimise opportunities for corruption. We note that the rollout of digital Occurrence Books stopped because t would have closed a vital corruption loophole. PRWG-K opines that police remain predatory not because they are under-resourced but because their values are suffocated by transactionalism, corruption and impunity. The use of technology will help; however, what is needed is new ideas around anti-corruption sanctions and integrity re-education.

Most important is the Inspector General of Police to lead from the front!

Vetting

PRWG-K supports the recommendation of vetting officers of the rank of Senior Superintendent of Police (SSP) and above. Because corruption and indiscipline are ubiquitous and affect all service levels, all officers should be vetted before being moved to a higher rank.

We note that as much as the last round of vetting led by the Johnston Kavuludi-led NPSC revealed the level of corruption, it was not impactful because it only focused on financial probity while ignoring suitability, professionalism, and human rights records. The vetting also lost credibility when public hearings and media coverage of the vetting of Traffic Unit Officers was suspended and further lost legitimacy and usefulness when the Kinuthia-led NPSC pardoned 300 officers not found to be suitable.

As such, we recommend that future vetting is intentional regarding the tools and considerations used and should consider existing complaints against officers, disciplinary records, human rights records, and financial issues. This must include input and information from EACC, IPOA, CAJ, KNCHR and civil society organisations.

Most importantly, the vetting process must meet the constitutional threshold of public participation, for the public are the consumers of policing services and know where the shoe hurts. Wellbeing and Mental Health Between 2016 and 2020, 65 murders and 57 suicides were reported by the National Police Service (NPS), indicating a murder rate of 13 per year and a suicide rate of 11 per year for the service. In addition to murder-suicides, there has also been an increase in public displays of frustration and stress by officers attached to different stations throughout the country.

There are several contributing factors to poor mental health, such as psychological stress owing to working conditions and nature of work, easy access to firearms, recruitment and training practices, discrimination and unfair treatment by superiors, involvement in crime, and attitude toward mental illness. The Police encounter crime scenes, bodies, and injuries. Also, they take statements from victims regarding crimes such as rape, defilement, murder, assault, etc. They absorb stress, which affects their mental health and coping ability, leading to burnout. As a result, some officers become depressed. Additionally, they suffer from mental health problems because of a lack of support and debriefing sessions.

The PRWG agrees that police officers need comprehensive health insurance that also caters for mental health issues. Moreover, a better monitoring mechanism is needed to flag those undergoing mental episodes and give them the care that they need. Such officers should not be given duties that require them to carry firearms.

Salaries and Benefits

The PRWG-K supports the proposal for better remuneration for police officers (40% over a period), as the taskforce recommends, which is subject to the Salaries and Remunerations Commission (SRC) recommendations. However, we caution that not all law enforcement agencies’ problems and dysfunctionality harken back to salaries and benefits, especially concerning services to citizens, accountability, and human rights. We reiterate that the police in Kenya remain predatory not because they are under-resourced but because, as a matter of culture, their values are suffocated by transactionalism, corruption and impunity.

We also support the improvement of housing conditions for police officers. In this regard, we think that the provision-based housing is no longer viable and recommend that the allowance-based housing policy of 2018 be retained with enhanced house allowances as the SRC may recommend.

Gender perspective

The PRWG-K lauds the progress that the Service has seen over the years concerning enhanced recruitment of women, the establishment of Gender desks to serve victims of

SGBV, and the inauguration of POLICARE meant to be a multi-agency-one stop victim support centre for SGBV. Our monitoring has established that POLICARE and gender desks are not adequately manned and funded, and we urge dedicated funding and manning of these initiatives.

Regarding recruitment, we recommend fidelity to the Career Progression Guidelines that speak to a one-third (1/3) recruitment and promotion at all levels. National Youth Service as a Pathway to Recruitment intothe Service

The PRWG-K notes the NYS’s contributions to the nation and the value it provides for the trainees who go on to do great things for themselves and the nation due to the quality of skills they learned at NYS. However, we disagree that the NYS should be construed as part of the disciplined forces or that it should be treated as a national security organ or militarised. We note that as per Article 239 of the Constitution, the National Security Organs in Kenya are only 3 namely: the Kenya Defence Forces (KDF), the National Police

Service (NPS), and the National Intelligence Service (NIS).

We further disagree with the taskforce that the NYS should be a pathway for service members to become police officers.

The PRWG-K position is that the mandate of youth empowerment is very important but completely different and distinct from the functions and mandate of the National Police Service. The PRWG-K has it on good authority that the NYS recruitment has been marred with irregularities such as favouritism and nepotism.

There are credible allegations thatsome senior politicians are given quarters of persons to be recruited into NYS. Making NYS a major pathway for appointment will ensure that such irregularly appointed persons have the upper hand in entering the NPS, thereby exacerbating the recruitment challenges.

We recommend that NPS applications be competitive to all qualified persons, noting that

serving as an officer is a larger calling and a national security issue.

CONCLUSION

PRWG-K lauds the taskforce findings and recommendations concerning policing in Kenya. We agree with the need to transform the NPSC and the NPS leadership and the finding that corruption is endemic within the service. We note that no solution was recommended to eliminate transactionalism and corruption beyond the call for the use of technology, abolition of police roadblocks, and restructuring the Traffic Police Unit. This

is despite corruption making the police an institution of pain instead of respite to Kenyans.

The PRWG-K finds that the report failed to factor in human rights as a central requirement of policing that the police and that needs urgent attention for policing to meet its constitutional mandate to Kenyans.

Last, we recognise President Ruto’s important step to establish the Task Force. It has provided an opportunity to examine policing and propose solutions.

Several imperatives obtain:

- It is imperative that the President now makes public the full report to enable all stakeholders to understand the findings and rally behind the more than urgent implementation process.

- Political good will from the highest office in the land will be critical for the success of this process.

- Competent and visionary leadership at the National Police Service, decoupled from partisan politics and grandstanding.

- To start with a national policing conference would be ideal to digest these findings and build momentum for reform.

[1] Section 10 (k) NPS Act – Inspector General shall issue guidelines on Community policing and ensure cooperation between the Service and the communities it serves in combating crime”

The Police Reforms Working Group (PRWG Kenya) is a consortium of 21 grassroots, national and

international civil society organisations (CSOs) working on police reforms since 2010. We have supported and advocated for police reforms in line with the 2010 Constitution and other laws that aspire to a professional, accountable, and human rights-compliant National Police Service (NSP). We are cognizant of the police reform journey, especially concerning where we came from, where we want to go as a country, and the various processes, institutions and organs created to achieve police reforms.- This statement is signed by members of the Police Reforms Working Group-Kenya, an

alliance of national and grassroots organisations committed to professional, accountable

and human rights-compliant policing. They include:

- Amnesty International Kenya

- Constitution and Reform Education Consortium (CRECO)

- Defenders Coalition

- Federation of Women Lawyers (FIDA- Kenya)

- HAKI Africa

- Independent Medico-Legal Unit (IMLU)

- International Centre for Transitional Justice (ICTJ – Kenya)

- International Justice Mission (IJM-K)

- Kariobangi Paralegal Network

- Katiba Institute

- Kenya Human Rights Commission (KHRC)

- Kenyans for Peace, Truth and Justice (KPTJ)

- Peace Brigades International Kenya (PBI Kenya)

- Shield For justice

Page 10 of 10 - Social Justice Centres Working Group (SJCW)

- Social Welfare Development Program (SOWED)

- The Kenyan Section of the International Commission of Jurists (ICJ Kenya)

- Transparency International Kenya

- Wangu Kanja Foundation

- Women Empowerment Link