There is general consensus that the pre-2010 Judiciary in Kenya was characterized by impunity, emasculation by the executive, and endemic corruption that had resulted in total loss of faith in the institution by the Kenyan public.

This was to be expected as executive high handedness controlled the appointment of judicial officers in a recruitment process that was as opaque as the judicial officers it produced. Many have painted the grim picture of the pre-2010 Judiciary.

The Committee on Constitutional Review Commission which compiled public feedback that informed the content of the 2010 Constitution recorded the following: ‘Serious allegations were made against the Judiciary, including inefficiency, incompetence and corruption. Similar sentiments had been expressed by a committee established by the Judiciary itself.

The most vivid picture was however painted by the Rtd Chief Justice Willy Mutunga who after 100 days in office had this to say; “We found an institution so frail in its structures; so thin on resources; so low on its confidence; so deficient in integrity; so weak in its public support that to have expected it to deliver justice was to be wildly optimistic. We found a Judiciary that was designed to fail. In shot the Judiciary was a high place with very low standards.

The recent appointment process of the Chief Registrar of the Judiciary has sparked concerns about transparency and fairness. In the past, the appointment of public officials without public participation was common practice.However, this approach is no longer acceptable in today’s democratic society.

While there may not be a specific legal requirement for the Judicial Service Commission (JSC) to conduct the chief registrars’ interviews in public, it has become a widely accepted practice across all branches of government, more so with the judiciary, to broadcast the vetting process of Judicial officers.

The importance of public scrutiny in such appointments cannot be overstated, especially considering the significance of the Chief Registrar’s role, which is equivalent to that of a High Court judge.

The procedural and substantive edicts on recruiting Judges is set out in mandatory terms in the Third Schedule to the Judicial Service Commission Act. The schedule is very prescriptive as it spells out the activities to be carried out and also sets the timelines.

This distinguishes the exercise of recruiting Judges as one of the most, if not the most, rigorous, open, and participatory recruitment carried out by a state agency. The participatory nature of the process is in congruence with the constitutional pronouncement that judicial authority emanates from the people.

The decision to conduct interviews for seven candidates in a single day, with the final candidate interviewed late into the night, raises serious questions about the fairness and thoroughness of the process.

It is widely recognized that interviewing candidates under such conditions can significantly impair their mental capacity and may not allow for a comprehensive assessment of their qualifications and capabilities.

Factors such as fatigue, time constraints, biases, and uneven attention across candidates interviewed throughout the day can all contribute to a less than ideal assessment process, casting doubt on the fairness of the selection criteria and outcomes.

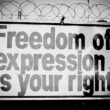

Moreover, the lack of public disclosure regarding the interview process goes against the principles of openness and transparency enshrined in Article 10 of the Kenyan Constitution. The public has a right to know how such crucial appointments are made and to have confidence in the integrity of the selection process.

The JSC, as a constitutional body entrusted with safeguarding the independence and integrity of the judiciary, should adhere to the highest standards of transparency and accountability. By conducting interviews behind closed doors and rushing through the process, the commission risks undermining public trust in the judiciary and its ability to uphold the rule of law.

Moving forward, it is imperative that the JSC revisits its appointment procedures and ensures that future interviews for key positions are conducted openly and transparently. This will not only enhance public confidence in the judiciary but also uphold the principles of good governance and accountability as outlined in the constitution.

The Author,Thuku Mburu is a lawyer and a Programme Officer at ICJ Kenya.