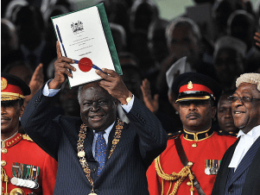

NAIROBI,Kenya – Fourteen years ago, after three decades of tireless struggle, Kenyans finally gifted themselves a new Constitution widely regarded as people-centred and people-driven. This historic moment was not just a legal milestone; it was a direct response to the deep-rooted misgovernance, human rights abuses, sham elections, and pervasive inequality that culminated in the disastrous 2007-2008 elections.

From this dark chapter in Kenya’s history, a collective realisation emerged: the Constitution was envisioned as a safeguard against the excesses of presidential power, which had been abused since independence to concentrate authority in the executive branch while cannibalising other arms of government. The judiciary, often seen as subservient to the executive, was particularly vulnerable, with judges appointed at the president’s discretion. The legislature fared no better, as the ruling party could easily manipulate parliamentary support by filling it with cabinet members and assistant ministers.

Thus, the constitution-making process was meant to address legal and institutional frameworks, land reform, poverty, inequality, unemployment, national cohesion, and the endemic issues of transparency, accountability, and impunity.

One of its most significant innovations was the creation of what has been termed the “fourth arm of government”, Constitutional Commissions and Independent Offices. These bodies were tasked with monitoring, promoting, protecting, and implementing critical issues such as land reform, human rights, judicial appointments, police oversight, elections, revenue allocation, and budgeting. By decentralising these functions, the Constitution sought to reduce the overconcentration of power in the presidency and ensure greater accountability. Have these bodies lived up to the expectations?

The Constitution also codified national values, providing a framework for all government actions. These values included patriotism, national unity, sharing and devolution of power, the rule of law, democracy, human rights, equality, integrity, transparency, sustainable development and public participation. These principles were not mere aspirational ideals but were meant to guide the interpretation and execution of government functions at all levels.

A whole chapter on leadership and integrity was dedicated to dictating the character and conduct expected of those in public office. This chapter sought to curb the impunity and corruption that had plagued Kenya for decades by setting clear standards for ethical leadership.

The Bill of Rights, another cornerstone of the Constitution, laid out the fundamental freedoms and human rights to which every Kenyan is entitled. These rights include socio-economic rights, such as access to adequate water, housing, education, and healthcare.

Certain rights were deemed non-derogable, meaning they could never be limited, such as freedom from torture, the right to a fair trial, freedom from servitude and slavery, and the right to habeas corpus. For rights that could be limited, the Constitution set strict parameters, ensuring that any limitations were reasonable in a democratic society, clearly defined in law, necessary, and proportionate. It also placed the burden of proof on those seeking to limit a right to justify such limitations.

The Constitution granted every Kenyan the legal standing to challenge any infringement or threat of infringement of these rights in the High Court, empowering citizens to hold the government accountable.

One of the most transformative aspects of the new Constitution was the creation of 47 county governments, designed to bring decision-making, power, and resources closer to the people. This devolution of power was meant to enhance local governance, ensure a more equitable resource distribution, and address certain regions’ historical marginalisation.

Fourteen years later, there is much to celebrate about Kenya’s constitutional journey. The framework established in 2010 has brought about significant progress in many areas, but challenges remain, particularly regarding transparency, accountability, and the persistent inequality plaguing the nation.

As Kenyans reflect on this anniversary, it is clear that while the Constitution laid a strong foundation, the work of building a just and equitable society is an ongoing process that requires vigilance, commitment, and continuous improvement.

The writer, Demas Kiprono is the Deputy Executive Director – ICJ Kenya. This article was first published on the Standard.