NAIROBI,Kenya – Since the early 1990s when multi-party democracy was restored, political compromise and dialogue have solved crises that endanger peace and stability. Whenever the country is on the brink of chaos, the political class must come together and negotiate deals that typically restore some degree of normalcy.

This was the case in 1997 when the Inter-Parties Parliamentary Group (IPPG) mechanism was established in response to nationwide protests that frequently turned violent due to police brutality.

The protests demanded legal reforms to level the political playing field before the general elections.

As a result of this mechanism, the Electoral Commission of Kenya (ECK) was expanded to include Opposition nominees. Other changes affected pubic order management, political organising, detention without trial, and free expression.

Despite these changes, Kenyans still hoped for a more comprehensive constitutional overhaul to redefine the relationship between the citizens and the State and reconfigure governance, human rights, and democratic principles. However, there were disagreements on how to carry out this process. The Kanu government favoured a Parliament-led process, while others wanted the people’s and civil society’s involvement.

In 2001, Prof Yash Pal Ghai was appointed to head the Constitution of Kenya Review Commission (CKRC). However, before taking the oath of office, he insisted that civil society and religious groups should be included in the constitution-making process.

This led to a robust and participatory constitution-making process in Kenya. Unfortunately, the political class hijacked the process, and the resulting “Wako Draft” was rejected by Kenyans in the 2005 referendum. This caused the dissolution of the Cabinet and the formation of a new one.

Furthermore, the Raila Odinga-led team was removed from the Mwai Kibaki government, which set the stage for the rifts that led to the 2007-2008 post-election violence. This violence caused the death of over 1,300 Kenyans, rape, internal displacement of hundreds of thousands, and injuries.

In response to the high levels of violence, destruction, and pressure from the international community, the political leaders engaged in negotiations mediated by former UN Secretary-General Koffi Annan.

This resulted in the signing of the National Accord and a power-sharing agreement. The accord established the position of non-executive Prime Minister, two Deputy Prime Ministers, and a large Cabinet consisting of over 40 ministers and numerous assistant ministers. Additionally, the National Accord introduced a plan for constitutional reforms and the formation of various commissions to investigate Kenya’s issues, and provide suggestions.

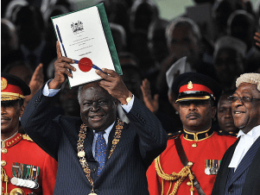

These commissions included the Kreigler Commission on Elections, the Waki Commission on Post-Elections Violence, the Ransley Commission on Police Reforms, and the Truth, Justice, and Reconciliation Commission. After a thorough constitution-making process led by the people, the Kenyan citizens finally approved the 2010 Constitution. The new Constitution aimed to address corruption, impunity, excessive executive powers, and human rights violations.

The protests that took place in 2018, led by the Opposition and resulting from the nullification of the 2017 General Election and repeat elections, caused another political crisis. This was eventually resolved through a surprise agreement between Raila and President Uhuru Kenyatta known as the Building Bridges Initiative (BBI).

However, the proposed constitutional and legal reforms that followed were criticised for being an unconstitutional hijack of the Constitution and were cut short by the courts.

Kenya is experiencing another constitutional change push after the crisis caused by the 2023 Azimio-led protests related to the cost of living. This has resulted in the formation of the National Dialogue Committee (NADCO), which has triggered a Constitution Amendment Bill. However, there are already concerns about the proposed changes and the possibility that some are unconstitutional. Are we expecting another BBI-type court battle?

The author, Demas Kiprono is the Ag. ICJ Kenya Executive Director. This article was first published on the Standard.