The country’s 94 prisons continue to grapple with congestion and financial burdens of taking care of inmates.

The correctional facilities have a holding capacity of about 27,000 prisoners but are currently holding in excesses of 54,000, which is more than double their capacity.

Half the inmates are convicts of petty offences and pre-trial remandees facing prosecution for minor offences.

A senior prisons official who is not authorised to speak to the press said congestion of correctional centres by convicts of petty offences and remandees is a systematic problem.

“Most end up serving longer sentences in prison while on trial than they would if convicted. I am not saying they are serving a sentence but they are in prison before they are convicted,” the officer said.

“You get a person who is accused of theft by relatives, for instance. Because the judicial system runs very slowly, once you are charged, you are given a first hearing date in three months. You come after three months and the investigators have not presented any evidence or witness, and therefore, are not ready to proceed, and you get another date after three months.

“You are lucky to appear in court for more than three times in a year and even those three appearances are not sufficient for trial. The second appearance after plea is always mention, the third time is an aborted trial after three months and they don’t have witnesses or only one or two witnesses have testified and the year is over.

“Where do you create a balance between the rights of the complainant and those of the accused person?

Much as you want to protect the rights of the accused person, the investigators would tell you that they have a prima farcie case, whose bearing is the allegations, just because someone alleged that you stole their chicken.”

RISING BACKLOG

The offences categorised as petty are defined by the state in terms of legislation mostly outside of the Penal Code and other minor offences that should not be criminal.

Most of the offences typically do not have a complainant other than the state and relate to the regulation of formal or informal economic activity, where a particular state interest is being protected, such as regulation of alcohol use, hawking, protection of the environment or enforcement of traffic rules.

Data from the 14 magistrate’s courts surveyed by the ICJ Kenya found 75,000 accused persons in two years, with a high proportion of less serious offences. There are 116 court stations in Kenya, which suggests more than 230,000 cases.

The ICJ report said if all cases were to be resolved in a year, it would require the current 455 magistrates to resolve 500 cases per year.

“This illustrates the pressure placed on the [criminal justice] system by the high number of referrals of petty offence cases,” the report reads in part.

Secretary of prosecutions at the office of the DPP Dorcas Oduor said when they visited Nairobi Area remand allocation on February 10, there were 2,500 inmates who ought not to have gone to court. The number rose to about 3,000 before they made their report in two weeks.

“The problem is once you have taken a plea and you have been taken to remand, it is not easy to just call for the file and dismiss the charges. We have been calling for the files from the police, reviewing them and going to court and making applications to withdraw, and we have done quite a number,” she said.

DPP’S INTERVENTIONS

Oduor said they are intervening by taking measures to limit the number of cases that end up in courts.

The ODPP is looking at the door through which the cases are coming in “because it is useless to go to prison to deal with petty cases without addressing the way they come in” to arrest them at that level.

She said that is the reason the prosecutors have been told to be diligent before they admit cases so that petty cases that should not go to court are dropped.

“We are also looking at crimes that we can address, such as traffic offences. Some of them are petty and should not be criminal in the first place. Even if they were criminal, it is not cost-effective to take people to remand. So the DPP is looking at that and will be issuing guidelines on how prosecutors will be dealing with traffic offences,” she said.

“We are also saying if there could be an easier way of people paying their fines or bonds because with traffic cases, people are not given time to pay. When you are arrested, they [police] want an equivalent of the fine, which is Sh10,000. If you don’t have it you are taken to court and go to remand. We want to look at other strategies, how we can expedite the process and make people, for example, be given time to pay the fines.”

Oduor said in some countries, after committing a petty offence, one is given two weeks to make up their mind whether they want to plead guilty or not.

“If you know you committed the offence then you easily plead guilty and you are given a paybill number to go and pay fines — that is what happens in Tanzania. But here it is criminal and it has to go to court,” she said.

Story Published by Star Newspaper on this link: https://www.the-star.co.ke/news/2018/05/16/remandees-detained-longer-on-trial-than-they-would-if-convicted_c1758043

Story By: JOSEPH NDUNDA @joseph_ndunda

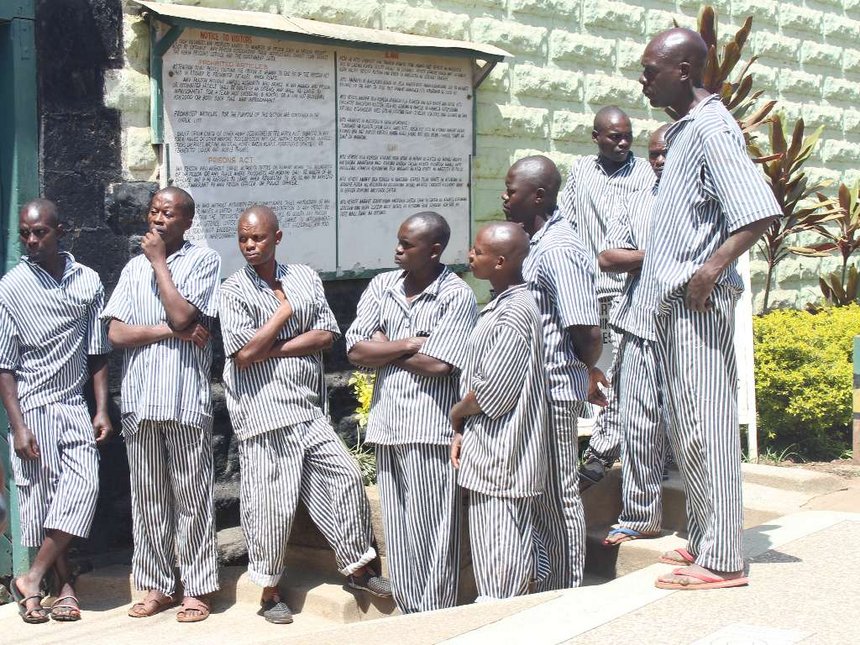

Photo: Inmates at Kodiaga Prison Kisumu