NAIROBI,Kenya – Femicide in Kenya has escalated into a national emergency, each brutal killing a chilling testament to a society that has failed its women. The rape, murder, and disposal of a 15-year-old girl in Land Mawe, in March, alongside the killing of another young girl for rejecting child marriage, are not mere tragedies; they are indictments of a broken system that continually abandons victims. These are not isolated incidents. They are the latest entries in an ever-expanding ledger of violence, each crime echoing the same harrowing reality: women’s lives remain expendable.

Kenya’s legal framework theoretically provides safeguards against such atrocities. The Constitution of Kenya, 2010, guarantees the right to life (Article 26), dignity (Article 28), and security of the person (Article 29). The Sexual Offences Act, 2006, and the Protection Against Domestic Violence Act, 2015, criminalize various forms of gender-based violence.

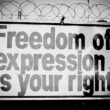

The Children’s Act, 2022, explicitly outlaws child marriage. Yet, these statutes, however well-crafted, are toothless in the absence of enforcement. Laws mean nothing when justice is a privilege reserved for those who can afford it. When perpetrators walk free while families grieve in silence, legal protections become little more than words on paper.

For years, femicide has thrived under a culture of impunity. Survivors and their families are forced to navigate a legal system riddled with delays, corruption, and outright negligence. Law enforcement officers, indifferent at best and complicit at worst, often dismiss cases as “family matters,” allowing abusers to reoffend with confidence.

Witnesses remain silent out of fear, knowing that the system offers them no protection. Court cases drag on for years, leaving families trapped in an endless cycle of trauma and despair. In the rare instances where convictions occur, lenient sentencing reinforces the idea that a woman’s life is worth little more than a fleeting headline.

Compounding this crisis is the political turmoil that has hijacked national discourse. The relentless reshuffling of government officials, the ceaseless power struggles, and the looming general elections have all but ensured that gender-based violence remains a peripheral concern.

Human rights issues are set aside as political survival takes precedence, and legislative actors who should be pushing for reforms are instead engaged in self-preservation. Meanwhile, an embattled judiciary faces increasing political pressure, casting further doubt on its ability to deliver justice. In a country where leadership is unstable and governance unpredictable, advocating for systemic change is a fight against shifting sands.

Beyond legal and political failures, societal complicity remains a formidable force sustaining femicide. Deep-seated patriarchy has conditioned communities to view violence against women as an unfortunate but inevitable reality. Families, fearing stigma, choose silence over justice. Survivors are interrogated more harshly than their abusers, their credibility picked apart while perpetrators benefit from a system designed to protect them.

The media, with its sensationalist reporting, reduces victims to statistics, failing to demand accountability or push for policy changes. Public outrage burns briefly before dissipating, replaced by the next crisis, the next scandal, the next distraction.

The innocent young girl brutally murdered and discarded Land Mawe and countless others before them should not fade into obscurity. They should not be reduced to fleeting news cycles or empty condolences from officials who will do nothing to stop the next killing. Each case is a failure of law, leadership, and society itself. Kenya cannot continue to operate as though the slaughter of its women is just another unfortunate reality.

The justice system must work, political leaders must act, and the public must refuse to let these crimes slip into forgotten history. Na tuake na undugu, let us stand as our sisters’ keepers, because their lives depend on it.

Beatrice Monari is an Advocate of the High Court and a Programme Consultant at the Kenyan Section of the International Commission of Jurists (ICJ Kenya). This article was first published on the People Daily Newspaper.